The Uncomfortable Truth About Your LLM in Production

Let me be direct: if you're running LLMs in production without explicit fact-checking mechanisms, you're not building a product—you're building a liability.

I've seen this pattern repeat across dozens of organizations. The demo goes well. The model impresses stakeholders. Everyone's excited about the "AI transformation." Then, three months into production, someone discovers the customer support bot has been confidently providing incorrect refund policies. Or the internal search tool hallucinated an entire compliance procedure that never existed. Or worse—the output was just plausible enough that nobody questioned it until real damage was done.

The problem isn't that your team made a mistake. The problem is that most engineering teams are applying web development mental models to AI systems, and those models fundamentally don't work here.

This isn't another article about prompt engineering tricks or choosing between GPT-4 and Claude. This is about system architecture—specifically, how to build LLM systems that are trustworthy by design, not by accident.

Why Hallucinations Aren't a Bug (They're the Feature)

Here's the part that many engineers struggle with: hallucinations are not something to "fix" in LLMs. They're a fundamental property of how these models work.

At inference time, an LLM is performing one operation, over and over:

P(next_token | previous_tokens, context)That's it. The model is answering: "Given everything I've seen so far, what token should come next to sound maximally plausible?"

Notice what's missing from this objective:

- No notion of truth

- No concept of "I don't know"

- No grounding in real-world facts

- No ability to distinguish authoritative sources from misinformation

- No temporal awareness (is this fact still current?)

When your model hallucinates, it's not broken—it's working exactly as designed. It's optimizing for linguistic coherence, not factual accuracy.

The Scale Fallacy

Many teams believe larger models will solve this. "GPT-5 will be better," they say. "Claude 4 has lower hallucination rates."

This is partially true and completely misleading.

Yes, larger models make fewer obvious errors. But they also produce more convincing wrong answers. They're better at sounding authoritative. They generate longer, more detailed explanations for things that aren't true. They cite plausible-sounding sources that don't exist.

The danger scales with capability.

A small model that says "Barack Obama was born in 1985" is obviously wrong. A large model that generates a detailed biographical timeline with slightly incorrect dates, plausible locations, and coherent narrative structure? That passes review because it feels right.

The Real Production Risk: Silent Failures

In demos and hackathons, hallucinations are amusing. Someone asks about a fictional celebrity, the model invents a biography, everyone laughs.

In production, they're corrosive.

The most dangerous failures aren't the obvious ones. They're the answers that:

- Look professionally formatted

- Include specific details that seem checkable

- Match the expected structure of a correct answer

- Sound confident and authoritative

- Pass casual human review

These errors propagate because no part of your system challenges them.

Once LLM outputs become inputs to:

- Automated workflows

- Decision support systems

- Other AI models

- Customer-facing interfaces

- Compliance documentation

- Financial reporting

...the cost compounds exponentially.

A Real-World Example

One team I consulted with had built an "AI analyst" that summarized customer feedback and generated strategic recommendations. The model would occasionally hallucinate product features that didn't exist but should exist based on customer complaints.

The business team loved it. They were acting on these "insights."

The problem went undetected for weeks because the hallucinations were logical. The model wasn't making random stuff up—it was inferring plausible product gaps and presenting them as facts. Only when someone cross-referenced specific customer IDs did the issue surface.

The lesson: A system that's usually right but never questions itself is more dangerous than one that's occasionally wrong but knows its limits.

What "Fact-Checking" Actually Means (And Why RAG Isn't Enough)

Most teams, when they encounter hallucination issues, reach for Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). It's become the default solution, almost reflexive.

RAG is valuable. RAG is not fact-checking.

Let me break down what these terms actually mean in production systems:

| Concept | Definition | What It Guarantees |

|---|---|---|

| Truth | Objective correctness in the real world | Nothing—this is the hard part |

| Factuality | Consistency with trusted source documents | Your sources might be wrong |

| Faithfulness | Not contradicting provided context | The model might cherry-pick or misinterpret |

| Verifiability | Claims can be traced to specific evidence | You can audit, but evidence might be wrong |

Understanding these distinctions matters because they map to different system architectures.

A model can be:

- Faithful to its context but factually wrong (if context is outdated)

- Factual according to sources but not truthful (if sources contain errors)

- Verifiable but incorrect (if it cites sources that don't support its claims)

Production systems must be explicit about which guarantees they're actually providing.

System Architecture: Where Fact-Checking Actually Lives

The question isn't whether to fact-check. It's where in your pipeline verification happens.

This determines your system's trust boundary—the point at which you're willing to accept model output as reliable.

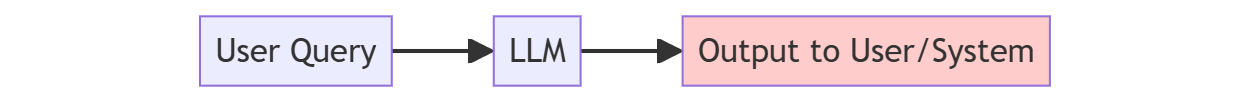

The Naive Architecture (Don't Do This)

If this is your architecture, you're trusting the model completely. Every hallucination goes directly to production.

When teams build this way, they typically try to fix problems by:

- Writing better prompts (helps marginally)

- Adding more context (helps marginally)

- Using a better model (helps marginally)

The problem isn't the model. It's that the architecture has no mechanism for disagreement.

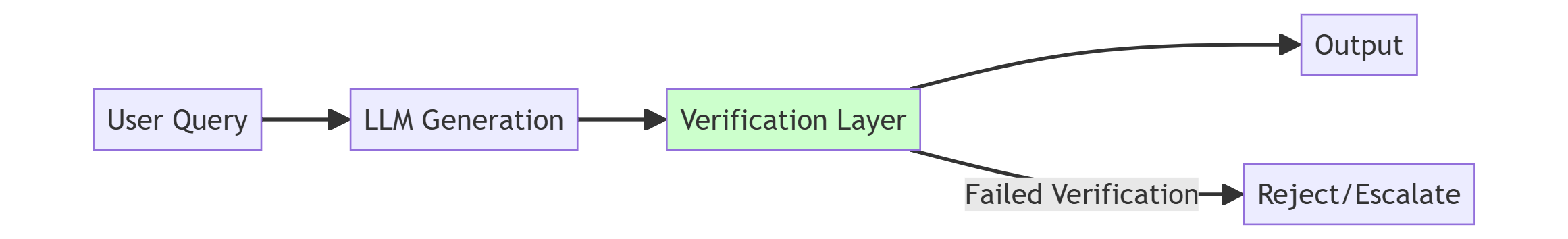

The Minimum Viable Architecture

This separates generation from acceptance. It's the smallest change that makes a meaningful difference.

But now the hard question: What does "Verification Layer" actually mean?

Four Verification Strategies (And When Each One Fails)

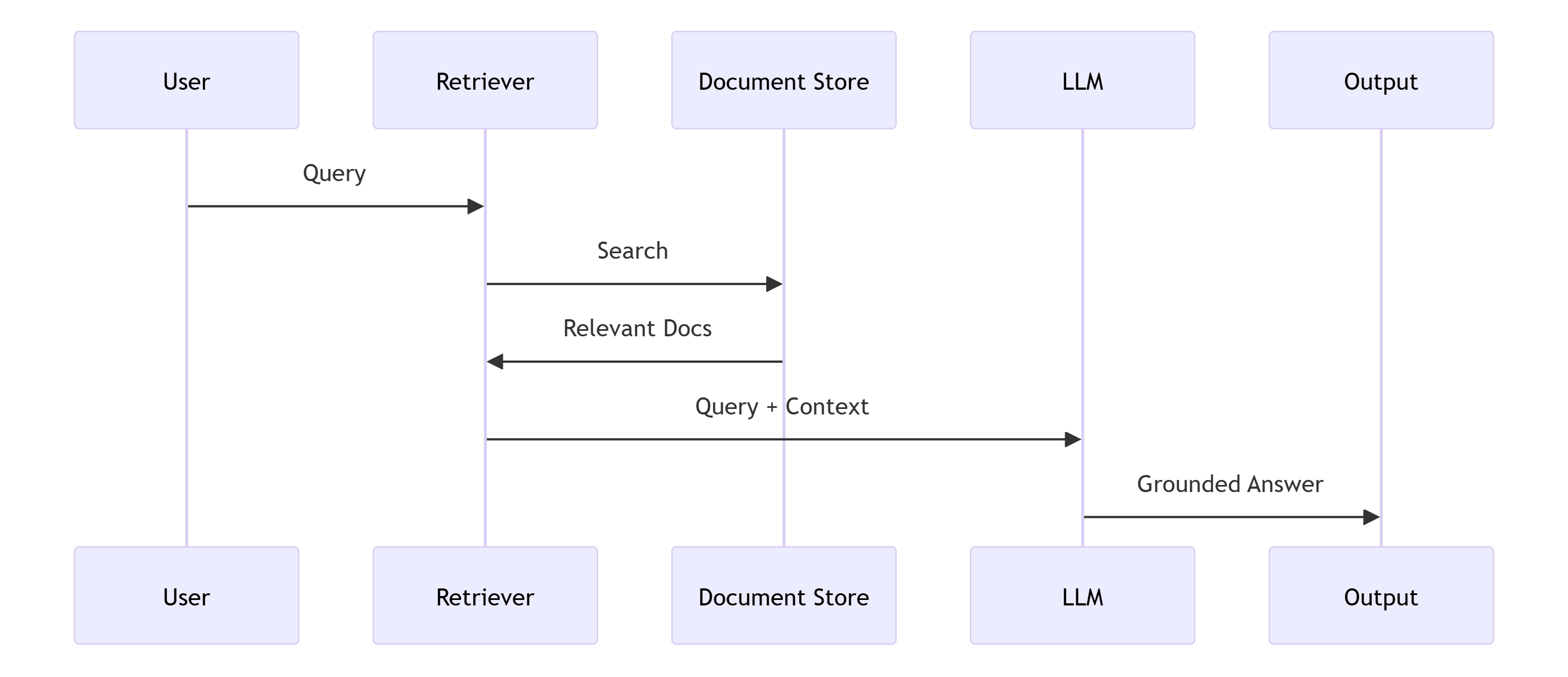

Strategy 1: Pre-Generation Grounding (RAG)

What it does well:

- Reduces parametric hallucinations

- Provides citation trail

- Works great for question-answering over known documents

Where it fails:

- Model can still hallucinate within retrieved context

- Retrieval quality determines output quality

- Can't verify reasoning or multi-hop inferences

- No guarantee model actually used the context correctly

Production reality: RAG is necessary but not sufficient. It constrains inputs; it doesn't validate conclusions.

I've seen systems where retrieval succeeded, documents were relevant, citations were included, and the answer was still completely wrong because the model fabricated logical connections between factual statements.

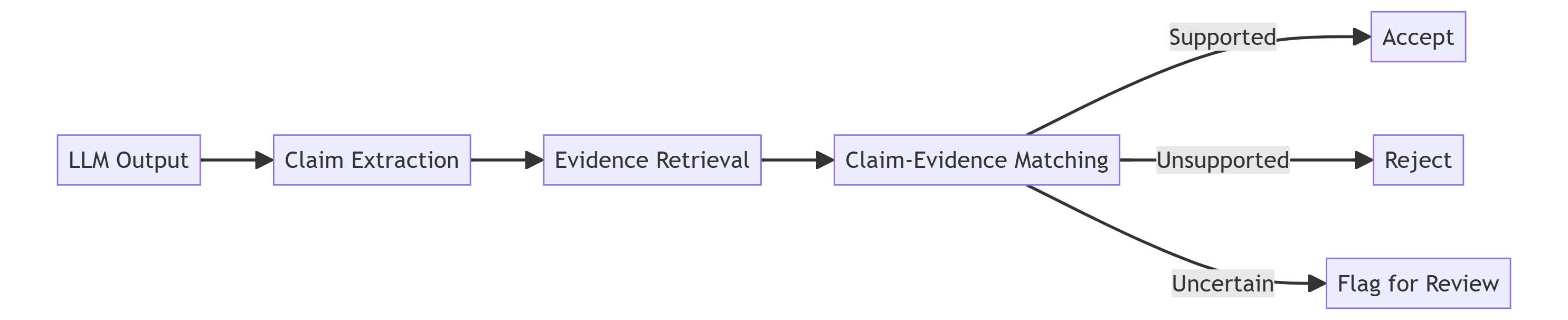

Strategy 2: Post-Generation Claim Verification

What it does well:

- Treats model output as hypothesis, not truth

- Makes verification explicit and auditable

- Catches fabricated reasoning

- Enables atomic claim-level checking

Where it fails:

- Significant latency overhead

- Requires robust claim extraction (also an LLM task!)

- Evidence retrieval might miss relevant sources

- Verification itself can hallucinate

Production reality: This is expensive and slow. It's also the most robust approach for high-stakes applications.

Think about how legal review works. Think about how scientific publication works. They're expensive, slow, and effective because they don't trust first-order outputs.

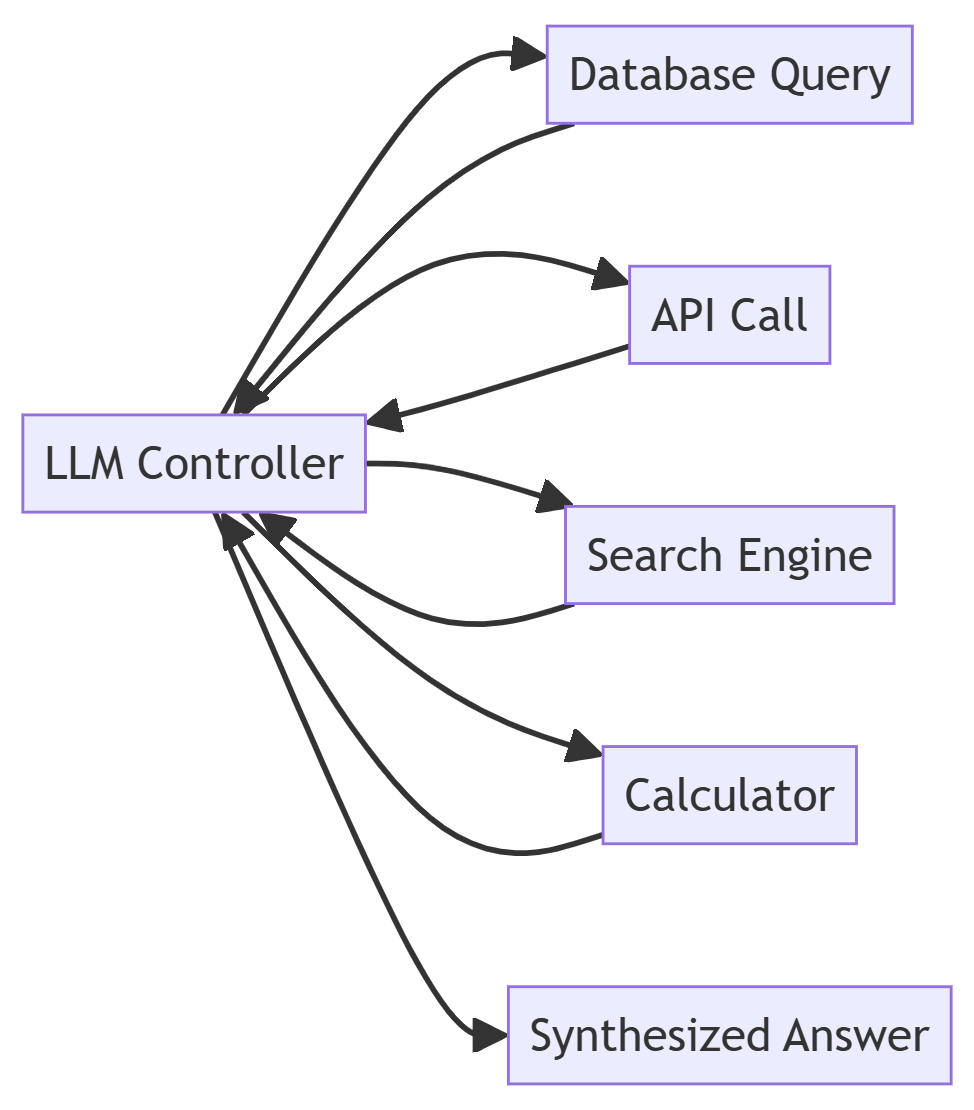

Strategy 3: Tool-Augmented Verification

What it does well:

- Facts live in systems, not model weights

- Model orchestrates but doesn't invent

- Verification is deterministic where possible

- Aligns with traditional software reliability

Where it fails:

- Limited to structured, queryable knowledge

- Tool selection is an LLM decision (can be wrong)

- Tool outputs require interpretation (also an LLM task)

- Doesn't help with reasoning tasks

Production reality: This is my preferred default for most production systems. Demote the model on purpose. Make it a coordinator, not a knowledge base.

If you need to know a customer's order history, query your database—don't ask the model. If you need current stock prices, call an API—don't rely on training data. If you need mathematical precision, use a calculator—don't let the model approximate.

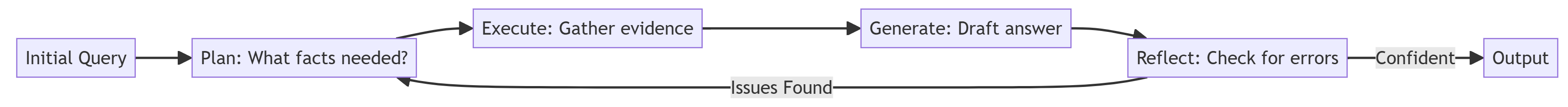

Strategy 4: Agentic Verification Loops

What it does well:

- Builds verification into the reasoning process

- Can detect and correct mid-generation

- Handles multi-step verification

- Makes failure explicit and recoverable

Where it fails:

- Extremely complex to implement and debug

- High latency (multiple generation cycles)

- Can loop indefinitely on hard questions

- Reflection quality determines success

Production reality: This works well for complex analytical tasks where accuracy matters more than speed. Financial analysis, medical decision support, legal research.

The key insight: failure is not an exception—it's part of the control flow. The system is designed to be wrong, detect it, and try again.

Implementing Claim-Level Verification: A Worked Example

Let me show you what robust verification actually looks like in code. This isn't production-ready (you'd need error handling, rate limiting, caching, etc.), but it demonstrates the architectural pattern.

from typing import List, Dict, Anyfrom dataclasses import dataclassfrom enum import Enumclass VerificationStatus(Enum): SUPPORTED = "supported" UNSUPPORTED = "unsupported" UNCERTAIN = "uncertain"@dataclassclass Claim: text: str claim_type: str # factual, numerical, temporal, etc. @dataclassclass Evidence: source: str content: str relevance_score: float @dataclassclass VerificationResult: claim: Claim status: VerificationStatus evidence: List[Evidence] confidence: float explanation: strclass FactChecker: def __init__(self, llm_client, retriever, verifier_llm): self.llm = llm_client self.retriever = retriever self.verifier = verifier_llm def verify_answer(self, question: str, answer: str) -> Dict[str, Any]: """ Main verification pipeline """ # Step 1: Extract verifiable claims claims = self._extract_claims(answer) # Step 2: Verify each claim independently results = [] for claim in claims: result = self._verify_claim(claim, question) results.append(result) # Step 3: Aggregate and make decision return self._aggregate_verification(answer, results) def _extract_claims(self, answer: str) -> List[Claim]: """ Extract atomic, verifiable claims from model output """ extraction_prompt = f""" Extract verifiable factual claims from this text. For each claim, identify: - The exact claim text - Whether it's factual, numerical, or temporal Text: {answer} Return as JSON list. """ response = self.llm.generate(extraction_prompt) # Parse response into Claim objects return self._parse_claims(response) def _verify_claim(self, claim: Claim, context: str) -> VerificationResult: """ Verify a single claim against retrieved evidence """ # Retrieve relevant evidence evidence = self.retriever.search( query=claim.text, context=context, max_results=5 ) # Use separate verifier LLM to judge verification_prompt = f""" Claim: {claim.text} Evidence: {self._format_evidence(evidence)} Does the evidence support, contradict, or remain uncertain about the claim? Provide: status (supported/unsupported/uncertain), confidence (0-1), explanation """ judgment = self.verifier.generate(verification_prompt) return self._parse_verification(claim, evidence, judgment) def _aggregate_verification( self, answer: str, results: List[VerificationResult] ) -> Dict[str, Any]: """ Decide what to do with the answer based on verification results """ unsupported = [r for r in results if r.status == VerificationStatus.UNSUPPORTED] uncertain = [r for r in results if r.status == VerificationStatus.UNCERTAIN] # Decision logic if len(unsupported) > 0: return { "status": "rejected", "reason": "Contains unsupported claims", "failed_claims": unsupported, "original_answer": answer } if len(uncertain) > len(results) * 0.3: # More than 30% uncertain return { "status": "needs_review", "reason": "Too many uncertain claims", "uncertain_claims": uncertain, "original_answer": answer } return { "status": "approved", "answer": answer, "verification_results": results }# Usage in production pipelinefact_checker = FactChecker(llm_client, retriever, verifier_llm)user_question = "What was Apple's revenue in Q3 2023?"llm_answer = llm_client.generate(user_question)verification_result = fact_checker.verify_answer(user_question, llm_answer)if verification_result["status"] == "approved": return verification_result["answer"]elif verification_result["status"] == "rejected": # Retry with different approach or escalate return handle_failed_verification(verification_result)else: # Route to human review return route_to_human(verification_result)Key architectural decisions here:

- Claim extraction is separate from verification - You don't want the same model grading its own homework

- Each claim is verified independently - Prevents error propagation

- Evidence is explicitly retrieved - No relying on parametric memory

- Verification has explicit confidence thresholds - You define acceptable risk

- Failures are routed differently - Rejected vs. uncertain get different treatment

The Self-Verification Trap

One pattern I see constantly in production: teams using the same model to both generate and verify its answers.

# Don't do thisanswer = llm.generate(question)verification = llm.generate(f"Is this answer correct? {answer}")This fails for a fundamental reason: if the model doesn't know something, asking it to verify won't help. You're just getting a second sample from the same distribution.

I tested this extensively on several benchmarks. Self-verification helps catch some errors (formatting issues, obvious contradictions, constraint violations). It doesn't catch knowledge errors.

If the model thinks "Barack Obama was the 45th president," asking it to verify this claim will likely return "Yes, that's correct" because that's what it believes.

When Self-Checking Works

Self-verification has value in specific contexts:

- Constraint checking: "Did I follow the required format?"

- Internal consistency: "Do my statements contradict each other?"

- Completeness checking: "Did I address all parts of the question?"

What it doesn't do: verify facts against reality.

Cross-Model Verification

Using different models for generation and verification is better but not a panacea:

answer = claude_sonnet.generate(question)verification = gpt4.verify(answer, question)This helps because different models have different failure modes. But both are still sampling from probability distributions, not checking facts.

The only reliable verification involves grounding in external sources—databases, APIs, human review, or specialized fact-checking systems.

Measuring What Actually Matters

You can't improve what you don't measure. But most teams measure the wrong things.

Metrics that lie to you:

- Overall accuracy percentage (hides failure modes)

- Average BLEU/ROUGE scores (measures fluency, not correctness)

- Model confidence scores (uncalibrated, often wrong)

Metrics that tell the truth:

1. Claim-Level Accuracy

correct_claims / total_verifiable_claimsBreak down by claim type (factual, numerical, temporal). This tells you where the model struggles.

2. Faithfulness Score

claims_supported_by_context / total_claimsMeasures whether model stays grounded in provided information.

3. Citation Accuracy

citations_that_actually_support_claim / total_citationsCatches models that cite sources but misrepresent them.

4. Recovery Rate

errors_caught_by_verification / total_errorsThis is crucial. Your verification layer is only valuable if it catches errors that would otherwise reach production.

5. Human Intervention Rate

cases_escalated_to_humans / total_casesTrack this over time. Rising rates might indicate your system is correctly identifying edge cases. Falling rates might mean you're shipping errors.

6. Time-to-Detection

How long between an error reaching production and discovery? This matters more than accuracy for trust.

The Trade-Offs Nobody Wants to Talk About

Every fact-checking approach has costs. Here's what they actually look like in production:

| Approach | Latency Impact | Cost Impact | Accuracy Gain | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No verification | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Simple |

| RAG only | +20-50% | +30-60% | +15-25% | Medium |

| Post-gen verification | +100-200% | +150-300% | +40-60% | High |

| Tool-augmented | +50-100% | +80-150% | +50-70% | Medium-High |

| Agentic loops | +200-500% | +300-600% | +60-80% | Very High |

There is no free lunch.

Every percentage point of improved accuracy costs something. The question is whether the cost is worth it for your use case.

When to Optimize for Speed

- Low-stakes applications (creative writing, brainstorming)

- Internal tools where errors are caught by humans

- Exploration and research workflows

- Cost-sensitive deployments

Strategy: RAG + basic self-consistency checks

When to Optimize for Accuracy

- Customer-facing applications

- Compliance and regulatory contexts

- Financial or medical decisions

- Systems that feed into automation

Strategy: Post-generation verification or tool-augmented approaches

When to Optimize for Auditability

- Legal tech

- Healthcare

- Financial services

- Government applications

Strategy: Full claim-level verification with evidence trails

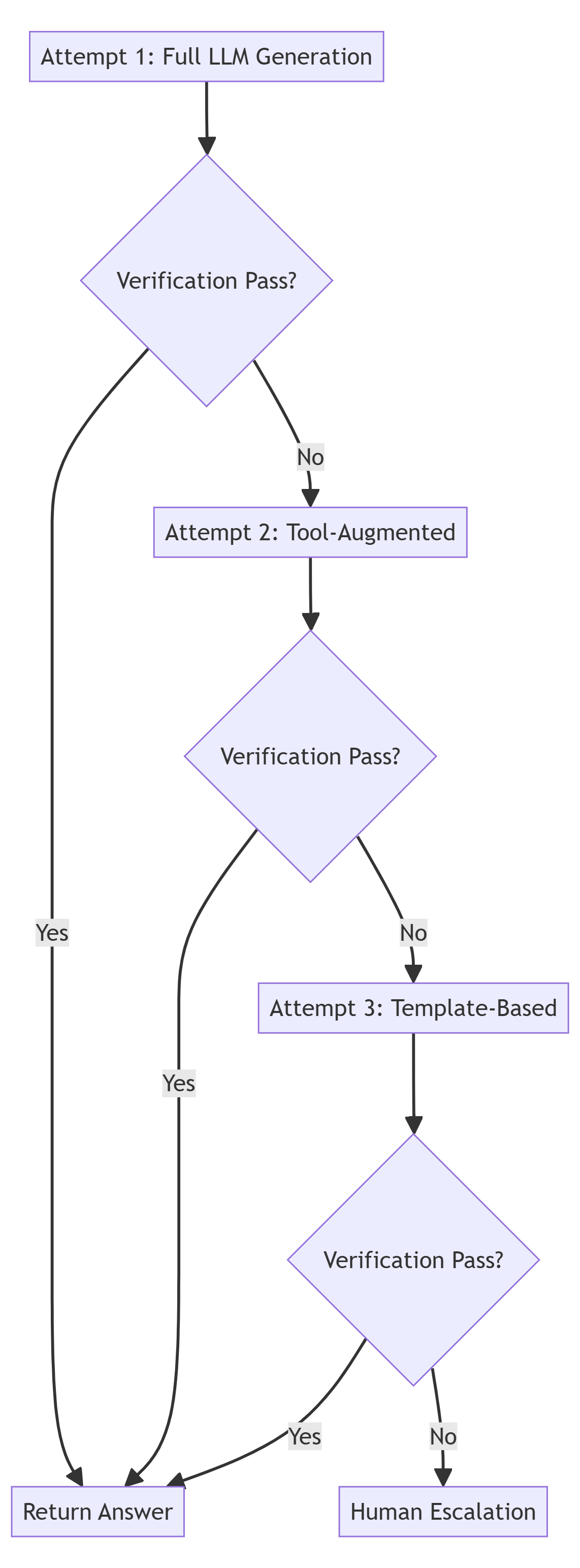

Production Patterns That Actually Work

After implementing fact-checking across multiple production systems, here are the patterns that consistently deliver value:

Pattern 1: The Confidence Budget

class ConfidenceBudget: def __init__(self, min_confidence=0.7, max_uncertain_claims=2): self.min_confidence = min_confidence self.max_uncertain_claims = max_uncertain_claims def should_accept(self, verification_results): avg_confidence = sum(r.confidence for r in verification_results) / len(verification_results) uncertain_count = sum(1 for r in verification_results if r.status == VerificationStatus.UNCERTAIN) return (avg_confidence >= self.min_confidence and uncertain_count <= self.max_uncertain_claims)Define acceptable risk levels explicitly. Don't aim for perfection—aim for "good enough with known failure modes."

Pattern 2: The Graduated Response

def handle_verification(result): if result.confidence > 0.9: return AutoApprove(result.answer) elif result.confidence > 0.7: return ReviewWithContext(result.answer, result.evidence) elif result.confidence > 0.5: return RegenerateWithConstraints(result.uncertain_claims) else: return EscalateToHuman(result)Not every output needs the same level of scrutiny. Route based on confidence.

Pattern 3: The Evidence Chain

@dataclassclass AnswerWithProvenance: answer: str claims: List[Claim] evidence: List[Evidence] verification_results: List[VerificationResult] generated_at: datetime verified_at: datetime verifier_version: strStore the full verification trail. When errors surface (and they will), you need to understand why they passed verification.

Pattern 4: The Fallback Hierarchy

Have degradation strategies. If the sophisticated approach fails, fall back to simpler, more reliable methods.

The Inconvenient Future

Here's my prediction: in five years, deploying LLMs without explicit verification mechanisms will be considered negligent engineering—like deploying web applications without input validation or deploying ML models without monitoring.

The industry is moving toward verifiable AI:

- Models that explain reasoning steps

- Systems that cite sources automatically

- Architectures that separate knowledge from reasoning

- Regulatory frameworks that require auditability

Organizations building production LLM systems today need to get ahead of this. Not because regulation will force them (though it might), but because silent failures compound.

Every uncaught hallucination erodes trust. Every confident wrong answer damages credibility. Every automated decision based on fabricated facts creates liability.

Practical Next Steps for Your Team

If you're running LLMs in production right now, here's what to do Monday morning:

Immediate (This Week)

- Audit your trust boundaries - Draw your actual system architecture. Where do you verify? Where do you just trust model output?

- Instrument verification metrics - Start measuring claim-level accuracy, not just overall quality

- Add basic confidence thresholds - Don't ship anything below 0.7 confidence without review

Short-Term (This Month)

- Implement post-generation spot-checking - Sample 10% of outputs and verify manually. Measure your error rate.

- Add explicit escalation paths - Where do uncertain cases go? Who reviews them?

- Build evidence trails - Start storing provenance for every answer

Long-Term (This Quarter)

- Redesign for tool augmentation - Move facts out of model weights and into systems

- Implement claim-level verification - At least for high-stakes outputs

- Train your team on verification patterns - This is a new skill set

Final Thoughts: Trust is Architectural

The biggest mental shift for engineering teams: you can't prompt your way out of hallucinations.

Better prompts help. Better models help. But neither eliminates the fundamental issue: LLMs optimize for plausibility, not truth.

The only solution is architectural. You must design systems that:

- Don't require trust in unverified outputs

- Make failures observable

- Route uncertainty appropriately

- Maintain evidence trails

- Degrade gracefully when confidence is low

This is harder than shipping a chatbot that sounds smart. It's also the difference between a demo and a product people can actually depend on.

Hallucinations aren't going away. But unverifiable AI can be. The question is whether your team builds for the demo or for production.

The industry needs fewer impressive demos and more boring, reliable systems. That's what fact-checking architecture delivers.

Resources and Further Reading

Academic Papers:

- TruthfulQA: Measuring How Models Mimic Human Falsehoods (Lin et al.)

- "Measuring and Improving Chain-of-Thought Reasoning in Vision-Language Models" (Chen et al.)

- "FActScore: Fine-grained Atomic Evaluation of Factual Precision in Long Form Text Generation" (Min et al.)

Production Guides:

- LangChain documentation on self-verification chains

- OpenAI's best practices for increasing factual accuracy

- Anthropic's guide to retrieval-augmented generation

Tools to Explore:

- LangChain's fact-checking chains

- LlamaIndex's response synthesis with verification

- Guardrails AI for output validation

- RAGAS for RAG evaluation

My Blog: For more deep-dives on production AI systems, LLM architectures, and practical implementation guides, visit ranjankumar.in

This article reflects patterns observed across multiple production LLM deployments. Your mileage will vary. Always benchmark your specific use case.